Between early 1692 and mid-1693, the Salem witch trials swept through colonial Massachusetts, with over 200 people accused of witchcraft and 20 executed.

While colonial authorities offered pardons and compensation to some of the accused as early as 1711, it wasn’t until July 2022 that Elizabeth Johnson Jr—the last of the convicted Salem “witches” whose name had not been cleared—was finally exonerated, bringing a long-awaited closure to one of history’s darkest chapters.

Let’s reimagine the dark past using AI:

The spark:

The events began in Salem Village (now Danvers, Massachusetts) in January 1692, when a group of young girls, including Betty Parris (the daughter of the local minister), began exhibiting strange behaviors—fits, convulsions, and violent outbursts.

Image credit: lexica.art

The girls, influenced by Puritan beliefs, claimed they were being tormented by witches. Local doctors attributed their condition to supernatural causes, further stoking fear.

Accusations and hysteria:

As panic spread, accusations of witchcraft began to escalate. The girls accused several local women, including a slave named Tituba, of practicing witchcraft and causing their afflictions. Tituba, after being interrogated and pressured, confessed, which only fueled the hysteria.

Image credit: lexica.art

Once accusations started, they spread rapidly, and many people, often women, were named as witches. The belief was that these witches had made pacts with the Devil, and their evil acts were said to be responsible for various misfortunes, from crop failures to illnesses.

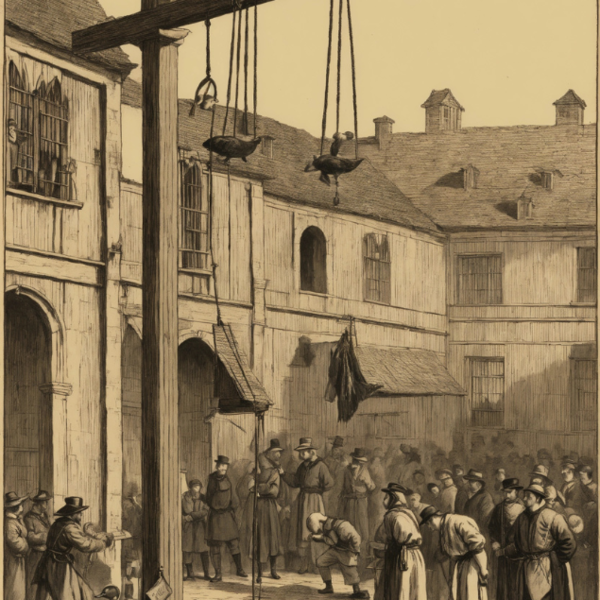

‘Touch test trials’

The trials began in earnest in the spring of 1692, with Judge Samuel Sewall, Reverend Cotton Mather, and others playing key roles in the prosecution. The accused were often subjected to intense and cruel interrogation methods, including “touch tests” (where the accused were forced to touch the afflicted individuals to see if their symptoms were relieved) and the infamous “swimming test” (where the accused would be thrown into water to see if they floated—believed to indicate guilt).

Image credit: lexica.art

Evidence in the trials was largely based on “spectral evidence“—testimony that the spirit or specter of the accused had been seen committing witchcraft. This form of evidence was highly controversial and unreliable, yet it played a significant role in the convictions.

Escalating panic:

As more and more people were accused, the trials took on a frenzy-like atmosphere. The authorities, believing they were fighting a widespread conspiracy of witches, allowed the trials to continue unchecked. Neighbor turned against neighbor, and personal grudges and rivalries often fueled accusations.

Image credit: lexica.art

The turning point:

By late 1692, the intensity of the trials began to wane. Public opinion started shifting, especially when prominent figures, like Reverend Increase Mather, voiced concerns about the legitimacy of the trials. The governor of Massachusetts, William Phips, intervened, halting the trials and later declaring that spectral evidence would no longer be admissible in court.

Image credit: lexica.art

The trials officially ended in May 1693. 20 people were executed, many others languished in prison, and the entire community was left scarred by the experience.

In the years that followed, many of the trial’s key figures, including judges, expressed regret for their roles, and several accused individuals were exonerated.

In 1711, colonial authorities issued a formal apology and offered restitution to the families of the accused, though it would take until 2022 for Elizabeth Johnson Jr, the last person convicted during the trials, to be posthumously exonerated.