The world over, the post-pandemic luxury boom is finally hitting the brakes. Prices of prestige watches, rare whiskies and fine wines had defied gravity for years after Covid. That run is now over in most of the world.

Across global markets, investors in such “passion assets” have seen prices slip 10-20% from their peaks. Primary and secondary markets have cooled, speculative premiums have thinned and what was once described as a luxury super cycle is settling into something more measured.

Yet, while the world cools, India is heating up. According to the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry, Swiss watch exports to India rose over 35.5% (valued at Rs 2,632.77 crore) in the first 10 months of 2025, over the same period two years ago, outpacing the top 30 markets worldwide.

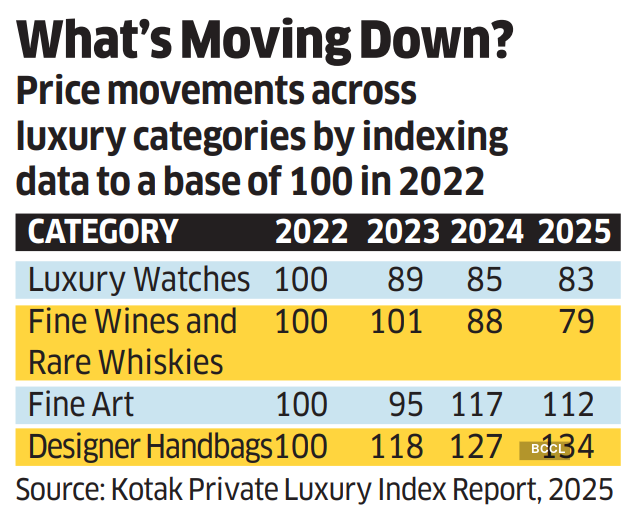

In effect, Indian buyers are stepping into a market that is correcting globally but expanding locally. Data from the Kotak Private Luxury Index 2025, by Kotak Private Banking, shows that while overall luxury spending continues to surge, asset prices have weakened.

The luxury watch index is down 17% since 2022, while fine wine and rare whisky have slipped to 79 from a base of 100. In 2026, the question for the affluent is simple —does this dip represent a warning sign for luxury as an asset class, or a generational entry point into premium assets?

QUIET RESET

To answer that question, it is critical to understand where the correction is coming from. It has little to do with demand disappearing. Instead, it reflects where and how prices are discovered.

“Luxury watches and fine wines are largely traded through open international secondary markets where prices reflect global demand and sentiment rather than solely Indian sentiment,” says a spokesperson of Kotak Private Banking in a response to ET. “Post-pandemic market normalisation, following a supply-squeeze boom during the pandemic, is a key driver for the declining growth of these markets.”

“Today, the demand for these goods has softened in US and China due to downturns in their markets, tighter household liquidity and, hence, shifting consumer priorities,” adds the spokesperson, calling the correction “primarily an outcome of this decrease in global demand”.

For industry veterans, the reset feels overdue rather than alarming. “What we are witnessing across categories is primarily a post-excess cooling rather than a structural devaluation of luxury,” says Abhay Gupta, a Gurgaon-based luxury strategist. “Corrections of this nature are cyclical and healthy.” More telling, Gupta says, is where value is reasserting itself. “This phase is also exposing a deeper bifurcation in luxury: between objects that carry enduring cultural, technical, or provenance-based value, and those whose pricing was inflated largely by hype.”

BLUE-CHIP TIME

In watches, the correction has been selective rather than sweeping.

“The market isn’t cooling overall; rather, trends have shifted,” says Giovanni Prigigallo, cofounder of EveryWatch, an online platform for watch databases. “Some watches dropped in value, but mainly in models that peaked during 2021.” What has held up, he says, are segments anchored in craftsmanship and scarcity rather than hype. “Independent brands are performing very well, as well as vintage and neo-vintage collectible watches.”

Kotak Private Banking’s data too suggests that models from Rolex, Omega and Patek Philippe continue to outperform, even as prices for several other brands remain under pressure, reaffirming the polarised nature of the market.

That is also visible in whisky.

Sukhinder Singh, cofounder of London-based Elixir Distillers, traces the current correction directly to how the category expanded during the pandemic. “Covid was an incredible time for the industry,” he says, “but sadly many products were launched for the investor rather than the true whisky lover. We now see that these collector bottles are falling in value, and I believe these will continue to fall.” What has proven more resilient, Singh says, is liquid-led authenticity. “The companies that release good honest whisky that tastes good and are at reasonable prices have not fallen, as they continue to be popular.”

Vinayak Singh, cofounder of The Dram Club, a community of whisky and spirits enthusiasts in Gurgaon, believes lack of access too is reshaping behaviour. “The price correction is largely a global phenomenon that hasn’t fully translated to India because of historical lack of availability. There is a pivot toward limited-edition Indian single malts,” he says, citing growing demand driven by “global acclaim, novelty and a serious case of FOMO”.

NEW OPPORTUNITIES

At the top end, the global softening has opened doors to top-tier private buyers.

“Something like this was unthinkable just two years ago. We are seeing aged barrels from cult distilleries like Clynelish, Lagavulin and Laphroaig come to the Indian market,” says Vinayak. “These ‘crown jewel’ names were impossible to access earlier.” Cask ownership, he adds, is seen as a long game. “For those looking at buying barrels, the current price correction is a once-in-a-decade opportunity.”

“Buyers picking up barrels from Scottish distilleries like Bunnahabhain and Benrinnes are taking a 7-10-year view,” says Vinayak, noting that some early buyers are already seeing notional gains, even as they prioritise liquid quality over quick exits.

Wine markets, long accustomed to cycles, reflect a similar unwinding.

“This correction represents a healthy and necessary market reset rather than a prolonged structural downturn,” says Aarash Ghatineh, chief revenue officer of London-based Cult Wines, a fine wine investment and advisory firm. He points to the extraordinary conditions of 2020-22, when “ultra-low interest rates, excess liquidity and restricted consumer spending drove capital into physical luxury assets”, pushing prices sharply higher.

As macro conditions reversed, prices corrected sharply, bringing valuations back to pre-2020 levels. Since late 2025, however, early signs of recovery have begun to appear.

“Since September 2025, the Liv-ex Fine Wine 100 index has risen 3.4%,” says Ghatineh, referring to the London International Vintners Exchange and pointing to valuation-driven buying returning after excesses were priced out.

“The current recovery is defined by fundamental value rather than speculative heat; demand is now anchored in the three pillars of the secondary market: verified provenance, optimal maturity and enduring brand equity.”

Similar correction cycles, notably 2008-09 and 2011-14, laid the foundation for a multi-year growth period, he says.

INDIA’S CONTRADICTION

What makes this phase particularly intriguing is India’s position within it. Despite global price corrections, “India is one of the fastest growing markets for Swiss watches… as India’s ultra-HNIs are increasingly channelling their wealth into exquisite luxury watches that embody both legacy and timeless value,” says the spokesperson of Kotak Private Banking, citing an over 37% growth compared with 2023.

On the ground, the demand is evolving. “The demand is increasing for hyped pieces as awareness sets in,” says Sameer Awasthi, founder of Indian Watch Connoisseur, a Delhi-NCR-based platform for trading in luxury watches. “However, the lines have blurred between hype horology and haute horology.” He is seeing a widening spectrum of interest. “There is an emerging curiosity about niche and offbeat timepieces that weren’t necessarily on the radar earlier.” Awasthi also points to a widening gap between seasoned buyers and first timers. “Seasoned collectors cash out with big gains.

First-timers usually chase the hype and almost always end up paying premium prices for hyped watches,” he says. That said, accessibility remains limited. “The market has corrected but still is far from a common man’s reach,” says Awasthi, pointing to how brands themselves have shaped pricing dynamics. “Brands are aware of pricing considerations and, therefore, retail prices have grown considerably. In turn, this has led to an increase in secondary market prices as well.”

A similar pattern is playing out in whisky, where India’s market has been historically driven more by consumption than speculation. “Indian collectors are still largely drinkers first,” says Vinayak Singh of The Dram Club. “The correction is bringing people back to the liquid rather than the label.” He adds that price softening has made entry more considered. “Buyers are spending more time understanding what they are buying, whether that’s a bottle to drink or a cask to hold; a label with long-term credibility and not just what might flip well.”

From a wealth-management perspective, the correction has not triggered an exit, but a pause for evaluation. “What we are seeing is a behavioural shift rather than a loss of interest,” says Nitaa Shivdasani, MD and head of HERitage, Waterfield Advisors’ wealth advisory for women. “Clients today are far more valuation-conscious, asking deeper questions around provenance, historical relevance and long-term desirability rather than simply following momentum.”

MOMENT OR MIRAGE?

Is this a time to buy? Wealth advisors are careful not to romanticise the moment. “Luxury collectibles should fundamentally be viewed as lifestyle and legacy assets first, not as core return generating investments,” says Shivdasani.

While recent corrections have improved entry points in select segments, she cautions against broad conclusions. “The current phase calls for discernment rather than deployment,” she says, adding that allocation decisions are increasingly being made with longer holding periods in mind. A broader capital markets lens reinforces that restraint.

“Luxury collectibles trend upwards over the long term largely due to low supply and expanding global wealth,” says Akhil Bhardwaj, founder of Alpha Capital, a Gurgaon-based family office and wealth management firm.From an allocation standpoint, Bhardwaj draws a clear boundary. “These items can offer diversification, provided the allocation is limited, typically up to 5%, as part of a satellite portfolio and not the core,” he says, adding, “Liquidity is low, valuation is nuanced, authenticity matters and upkeep costs, from cellaring whisky to maintaining watches, are real.”

A shift in mindset is precisely what corrections tend to produce, according to Gupta. “Price corrections tend to cleanse the market,” he says. “They separate the impulse buyer from the committed collector.”

Globally, watch markets reflect that same recalibration.

“For first-time buyers, it’s important to avoid extremes,” says Prigigallo of EveryWatch. “Chasing what was fashionable during the peak years rarely ends well.” The risk, wealth advisors note, lies in mistaking a price reset for a guaranteed upside.

“Passion assets are not substitutes for traditional investments,” Shivdasani says. “They work best when funded from surplus wealth and aligned with personal interest rather than return expectations.”

The bottom line: For India’s affluent who are truly interested, the opportunity may not lie in chasing the next supercycle, but in collecting with conviction while the rest of the world recalibrates.