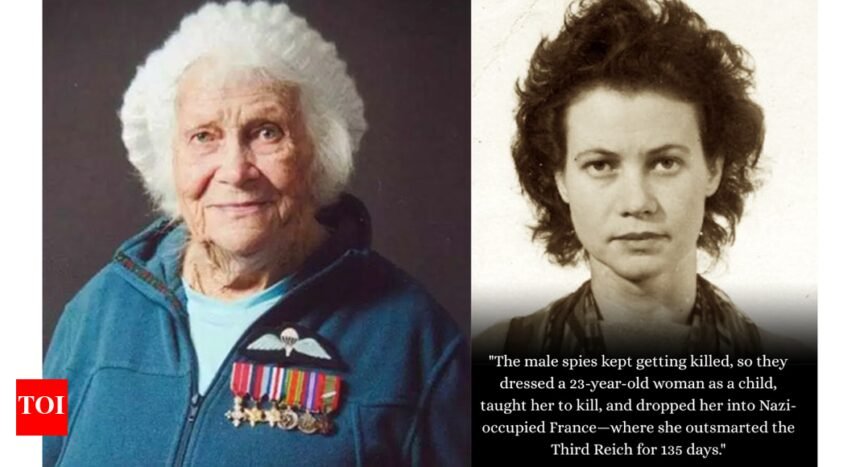

Phyllis “Pippa” Latour Doyle died in October 2023, aged 102, the last surviving female agent of Winston Churchill’s Special Operations Executive, the secret army that helped turn the tide of the Second World War.Two years on, her story is being rediscovered as a reminder of what true heroism once meant, quiet, selfless, and without audience. In a world where the word hero has been dulled by vanity and spectacle, Phyllis Latour stood apart, as a reminder of what true heroism once meant, Latour knew capture meant torture and death, yet she volunteered to parachute into Nazi-occupied France, driven not by glory but by duty. Her courage and restraint helped shape one of the war’s most decisive moments, and she carried the secret of it for more than fifty years.

The girl who outsmarted the Reich

It was May 1944. Five days before the D-Day invasion, a 23-year-old woman stood at the open door of a bomber aircraft, staring down into the darkness of occupied Normandy. The wind tore at her uniform; her parachute straps cut into her shoulders. Below her lay a landscape crawling with German troops. Her name was Phyllis Latour, codename Geneviève. And in minutes, she would jump. The men who had been sent before her were dead. Captured, tortured, executed. The Gestapo had become alarmingly efficient at hunting Allied agents. But the Special Operations Executive needed someone the Germans would never suspect, someone who could move unseen, blend in, and gather the intelligence that would decide the fate of the invasion. They chose a young woman, small, French-speaking, and, as one trainer noted dismissively, “childlike and naïve”. It would be a fatal misjudgement, for the enemy.Before she ever set foot in France, Latour was remade in Britain’s secret training schools. By autumn 1943, she was learning Morse code, survival and weapons handling, and the brutal routines of fieldcraft demanded of Churchill’s secret army. Her early reports dismissed her as “simple-minded” and “childlike”, but she endured every course, hand-to-hand combat, coded transmission, mock interrogations, with quiet determination. “It was unusual training, not what I expected, and very hard,” she later recalled. “They told me I could have three days to decide, but I said I’d take the job now.” By the time she finished, the naïve recruit was gone. In her place stood Geneviève, the spy who would outsmart the Reich and outlast them all.

Behind enemy lines

Parachuting into the fields of Normandy, Latour buried her equipment and became “Geneviève”, a fourteen-year-old French peasant girl selling soap from her bicycle. Her disguise was perfect: patched clothes, a shy smile, a soft provincial accent. The soldiers she passed on country roads saw only an innocent child, never suspecting that her ribbon of silk concealed the codes of a British spy. Every errand was reconnaissance. Every conversation was intelligence gathering. She cycled through checkpoints, chatting idly with German guards, memorising details, troop movements, ammunition stores, fortified positions. Then, when it was safe, she would disappear into the woods, unpack her wireless, and tap out her findings to London in Morse code. Her courage was astonishing. Each message risked death. German radio detection vans patrolled the countryside, able to trace a signal in minutes. To survive, she had to keep moving constantly, never transmitting twice from the same place, never staying longer than a night. Once, two soldiers burst into the house where she was transmitting. Calmly, she closed her set, folded it into its case, and pretended she was packing. “I told them I had scarlet fever,” she later recalled. “They left very quickly.”

One hundred and thirty-five days

For 135 days, Latour cycled across Nazi-occupied France. She sent 135 coded messages to London, more than any other female agent in France. Those dispatches guided Allied bombers, exposed German supply routes, and revealed troop concentrations ahead of D-Day.Lives depended on her precision.The Resistance she served was in constant peril, striking at railway lines and supply convoys to stall the German advance. Every act of sabotage demanded fresh supplies from Britain, weapons, radios, and parachute drops, and it was Latour’s coded transmissions that made those deliveries possible, pinpointing drop zones and bombing targets deep inside enemy territory. And for four months, she never made a mistake. Her ingenuity saved her life more than once. When German soldiers stopped her and demanded to search her belongings, one officer pointed to her hair ribbon. Without hesitation, she untied it, letting her hair fall loose around her shoulders. The silk containing every secret code she had used hung in plain sight, and the soldiers, convinced she was harmless, waved her through. It was an act of composure that encapsulated her brilliance: quick thinking, calm under threat, utterly fearless.

The war ends, and silence begins

Paris was liberated in August 1944. Phyllis had survived four months behind enemy lines, outlasting most of her male counterparts several times over. When the war ended, she returned to England quietly, without ceremony. Her service earned her the Member of the Order of the British Empire, the Croix de Guerre, the France and Germany Star, and later, in 2014, the Légion d’Honneur, France’s highest honour. Yet she never spoke about her missions. She married an Australian engineer, Patrick Doyle, and together they moved across Kenya, Fiji, Australia, and finally New Zealand, raising four children. To them, she was simply Mum. The war was never discussed. It was not until the year 2000 that her eldest son stumbled upon her name in a list of SOE agents and asked her directly. “Yes,” she said quietly. “I was a spy.” And that was all.

The woman behind the legend

Born in South Africa in 1921, Phyllis had known hardship early. Orphaned at three, she was raised by relatives in the Belgian Congo before being sent to England in 1939 to complete her education. In 1941 she joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force as a flight mechanic, and by 1943 had volunteered for the Special Operations Executive. Her training reports were hardly promising: “bright, eager and plucky,” one read, “but with no grasp of the realities of life.” She proved them spectacularly wrong. Clare Mulley, historian of female SOE agents, once noted that male officers often underestimated women trainees. Latour, she said, “gave exceptional service in France, her performance contradicted every line of her early assessment.” It is precisely that underestimation that makes her story so compelling today. In a time when women were rarely given such trust, Phyllis carried a nation’s hopes across occupied Europe and returned without asking for recognition.

A quiet legacy

When France honoured her in 2014, she was 93. At the ceremony, she seemed almost embarrassed by the attention. “I just did my job,” she said softly. Her death in 2023 marked the end of a chapter in the history of British intelligence, she was the last of thirty-nine female SOE agents to have served in France. Two years on, as her story resurfaces, it does so not merely as nostalgia but as a reminder: that courage can look like a young woman on a bicycle, pedalling past soldiers, smiling politely, and changing the course of history with every turn of the wheel.